As an internationally renowned oncologist, Dr. Ben Corn knows “it’s much sexier to pursue a cure for cancer than to try and instill hope.”

“But I don’t think it’s any less gratifying,” he says.

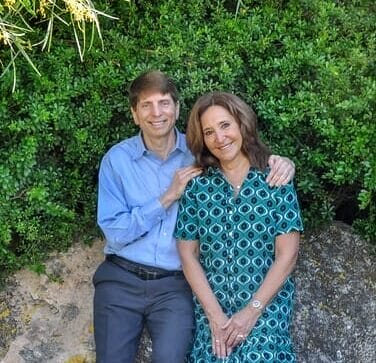

Corn is a professor of oncology at the Hebrew University School of Medicine in Jerusalem. He and his wife, Dvora, a family therapist, co-founded Life’s Door, an Israeli-American nonprofit committed to addressing the emotional needs of patients, as well as the family members and professionals who care for them. In May, Corn launched the Institute for the Study of Hope, Dignity, and Well-Being at Hebrew University.

Corn will present “Hope Is Real … and Essential” at the Cindy Wool Memorial Seminar on Humanism in Medicine on Thursday, Feb. 5.

The event will be held at the University of Arizona Health Sciences Innovation Building,

1670 E. Drachman St., beginning with a reception at 5 p.m. The lecture will also be available on Zoom.

Corn, who grew up in Brooklyn, New York, decided to study medicine at age 11, after his father died from prostate cancer. His aim, naturally, was to find a cure.

But when he was an oncology trainee in a Philadelphia hospital, he witnessed a brusque encounter between a professor and a patient that brought back memories of the way his father’s case was mishandled, at least from an emotional standpoint.

“No one recognized any stresses that dad might have been dealing with, and certainly none of the issues that my mother and siblings were contending with,” Corn says. “And so I began to understand and nurse the idea that something had to be done.”

After making aliyah in 1997, Corn and his wife started Life’s Door in 2004. The initial target audience was patients with cancer, he says, noting that in “The Anatomy of Hope,” Harvard Medical School professor Jerome Groopman says all patients crave hope, whether they are contending with advanced lung cancer or early breast cancer.

Corn believes the Israeli environment facilitated the establishment of Life’s Door.

“It will sound cliché, but it’s really very true, that in a country with a national anthem that’s no less than ‘Hatikvah,’” he says, hope is a core attribute of Israelis and Jewish people. In an environment where the majority of his patients, perhaps 80%, were Jewish, there was more receptiveness to the idea of instilling hope.

Hope doesn’t always mean a cure. “Hope is based on choosing a goal and a pathway and having the motivation,’ Corn explains, citing the model developed by Professor Rick Snyder of the University of Kansas, which underpins all of Life’s Door’s programs.

Corn recalls a patient with pancreatic cancer he met while covering for another doctor. Although the patient initially responded well to several experimental therapies, eventually they ran out of options. Corn and the surgeon had to tell the man he had about six months to live.

The sadness on the patient’s face was evident, but he told the doctors, “It’s not what you think.” He explained that for the past six and a half years, he’d been engaged in the study of a daily page of Talmud, and he was going to come up short by half a year. Corn asked if he’d be willing to study two pages a day, and when the answer was yes, interceded with the hospital rabbi to make that happen.

“I have a picture of him. He’s a French immigrant, with his arms outstretched as he’s exulting. He called it his Arc de Triomphe triumph pose,” Corn says, taken on the day he completed the study of the Talmud, which was about three weeks before he died.

Although Life’s Door started with cancer patients, it quickly branched out to other life-changing diseases, helping people learn to live with their new reality.

“We went through different pilot projects,” Dvora Corn says, encompassing communication within the family and the healthcare team, as well as various things “that people dealt with in terms of planning the rest of their life, and particularly their end of life, if it was a disease that was non-curable.”

Having developed and honed those mechanisms, she explains, Life’s Door now trains teams in both healthcare and community environments, from youth groups to the Israeli prison system.

Life’s Door helped people contend with the pandemic, Dr. Corn adds. “Suddenly people were more receptive to hearing what we had to say, because everyone on some level was thinking thoughts that they didn’t believe they would be entertaining, and it was just foist upon us.”

And in the past two years, Life’s Door has helped people deal with the effects of the Oct. 7 attacks and subsequent war, which provoked a range of trauma responses, from sleep disturbances to eating disorders to substance abuse.

The new Institute for the Study of Hope, Dignity, and Well-Being at Hebrew University is expanding Life’s Door’s efforts even further, with nearly 60 projects with collaborators in Canada, Australia, Japan, and the UK, among other international partners, Corn says.

Some people are understandably skeptical, Corn says.

“I think the only way that we can neutralize any of the doubt is to say, well, look what hope has done in a variety of settings, and most people sense that. But when you can substantiate the claims with actual statistical bona fides, it strengthens the case,” he explains.

The institute’s commitment to training “the next generation of people who provide these skills of how to become more hopeful” includes fellowships, scholarships, and taking part in programs such as the Cindy Wool Memorial Seminar.

One more aspect that speaks to the power of hope, Corn says, is that close to a third of their collaborators around the world are Muslim.

“I bring that up because it’s remarkable that even in the period that we’re living in right now, not one of them has checked out. There has been no experience at all resembling academic boycott for this work.

“It’s a testimony to the power of hope to bridge divides,” he says.

To register for the Cindy Wool Memorial Seminar in Humanism, click HERE.