Last month, the Tucson Jewish History Museum & Holocaust Center unveiled a new way for visitors to hear from Holocaust survivors: “Intimate Histories in 3D.”

The project uses volumetric capture technology to create three-dimensional recordings of survivors that can be viewed on tablets and personal devices.TJMHC created the project in collaboration with the University of Arizona Center for Digital Humanities and Holocaust survivors living in Southern Arizona.

Ten local survivors and two second-generation survivors participated.

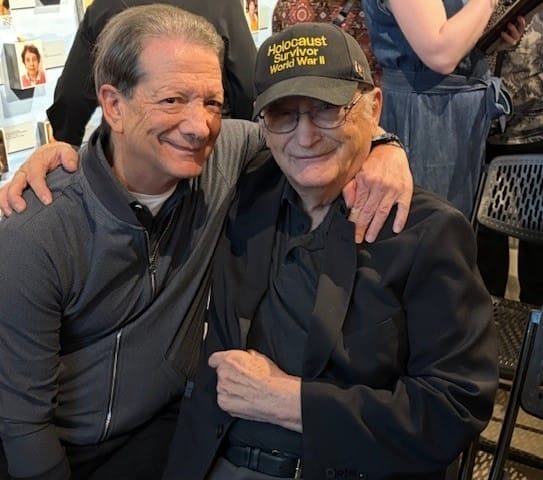

“This project is one of the most important we have ever done. This project keeps us alive for years after we are no longer here,” says Andrew Schot, a 94-year-old survivor from Amsterdam who often gives presentations to school tours and other groups at TJMHC.

QR code prompts to access the 3D recordings are scattered throughout the Holocaust Center, linking the recorded comments to various exhibits.

For example, one recording of Rosie Kahn, a museum docent who is a member of the second generation, is featured near the “Suspended Lineage” exhibit of photos that hang from the Holocaust Center’s rafters.

Kahn’s 3D image invites visitors to look up at the photos, which, she explains, are of family members of the survivors whose photos make up one wall of the center.

“These are people who did not survive the Holocaust. And when you look up there, we talk about six million people, six million Jews being killed during World War II. But if you look up there, you see many children, and if you figure that each one of those children would have had a family and more children, you realize that it’s way, way more than six million people that were really destroyed in the Holocaust,” her 3D image says.

“When I look up there, I feel really sad, because I have no pictures to put up there,” the 3D recording continues, as Kahn explains that she lost nine aunts and uncles, grandparents, cousins, a half-sister, and two half-brothers, and has no idea what any of them looked like, because no photos survived the war.

There are several 3D recordings of Kahn in other locations in the Holocaust Center.

The 3D project, TJMHC Executive Director Lori Shepherd says, is a new way to present and preserve Holocaust survivor testimony for the time when the survivors are no longer here to speak for themselves.

“We have been facing the twilight of our survivor population for a very long time,” she says.

The youngest survivors are now in their 80s.

The other second-generation contributor is Raiza Moroz, director of Holocaust survivor services at Jewish Family & Children’s Services of Southern Arizona, who immigrated to Tucson from Belarus in 1996.

People don’t often realize that Moroz is a “2G,” says Shepherd, who adds that two of the 10 first-generation survivors included in the project, Adelya Plotkin and Valentina Yakorevskaya, are also from the former Soviet Union.

“It was really important to us, because the Soviet Jewry, the Soviet Holocaust survivors, they’re usually really reluctant to share their stories,” Shepherd explains, adding that their history “doesn’t fit as neatly into the timelines of most Holocaust museums.”

TJMHC Board President Sharon Glassberg, who is also coordinator of Holocaust survivor services and Jewish inclusion at JFCS, called the 3D project “amazing,” a way of “keeping the past alive to forge a better future.”

“As technology evolves, so does the way we engage with difficult histories. Projects like this help equip educators and communities to address not only what happened in the past, but why these lessons remain urgently relevant in the present,” says Molly Dunn, Ph.D., education associate at Jewish Philanthropies of Southern Arizona.

“For a community like Tucson, where both our K-12 schools and local university have been working to address ongoing concerns around antisemitism, it’s important for learners to understand the Holocaust not as an isolated event but as part of the longer story of a people,” Dunn adds. “Volumetric recordings support that understanding by allowing students to encounter survivors not just as historical figures, but as real people with families, culture, and continuity. Seeing a survivor tell their story in three dimensions makes the history feel connected to the present — and helps explain why Jewish identity, memory, and resilience still matter today.”

Museum staff were excited when they learned that the African American Museum of Southern Arizona was creating a 3D project with the UA Center for Digital Humanities, Shepherd says.

They met with Bryan Carter, Ph.D., director of the UA center, “and from the very beginning, we just said, this is going to be a fantastic opportunity for our survivors, yes,” Shepherd says.

Carter explains that to make a volumetric capture recording, “We surround an individual with depth-sensing cameras, and we can record them all around. It basically records a 3D version of that person, so that when you scan a QR code, you can actually walk around the person and see them in 3D or volumetrically, as if they were actually standing in front of you.”

The 3D recordings are holograms, but they differ from the Holocaust survivor holograms at the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center, which can provide pre-recorded answers to questions from visitors.

The survivors in Illinois were interviewed over a period of a year, Shepherd explains, to record answers to a multitude of questions. Those holograms also cost $1 million or more per survivor.

Tucson’s museum, Carter says, “wanted to have it be a bit more natural, as opposed to these sort of pre-scripted questions that people ask. They wanted it to be more of a story that people were telling about various aspects of their experiences as a survivor.”

Bertie Levkowitz, another participant in the 3D project, was born in the Netherlands in 1942 and hidden with a series of non-Jewish neighbors, members of the Dutch underground.

“When you can get first-hand information, original source,” that is the most meaningful, says Levkowitz.

The 3D recordings are much shorter than her audio recording featured in the center’s Righteous Among the Living exhibit, Levkowitz notes.

“My guess is that gets a little long for casual visitors to listen to the whole thing, unless they’re particularly interested in that person,” she says, making the brief 3D recordings more accessible.

Young people like to play with technology, she adds, so she hopes younger visitors will tap into the 3D recordings.

Gary Monash, a local gastroenterologist, funded “Intimate Histories in 3D.”

Shepherd explains that survivor Sidney Finkel brought Monash, who is his doctor, to tour the Holocaust Center, which led to him funding three projects over the past three years, including providing copies of Finkel’s book, “Sevek and the Holocaust: The Boy Who Refused to Die” to all students who visited over the course of a year, and funding an extra booth for TJMHC at the Tucson Festival of Books, where people could stop to listen to survivors tell their stories.

This year’s project, the 3D recordings, is still in the beta test phase, Shepherd notes, with museum staff and volunteer docents refining how they assist visitors in accessing the holograms.

When Levkowitz, who is training as a docent, tried out the QR code for one of her recordings, “I did find myself sort of like a Chagall, sort of floating in the sky,” she says.

Nevertheless, “I think they’re doing the right thing, to try to preserve some of these stories,” she says.