Robert G. Varady’s father, László Weisz (“Laci,” pronounced “Lutzee,” to family and friends), cultivated a reputation as a raconteur. Varady grew up on Laci’s stories of business prowess in pre-war Budapest and survival during World War II – all of which Laci attributed to his quick wit, connections, and fierce determination, plus a pinch of luck.

Robert G. Varady’s father, László Weisz (“Laci,” pronounced “Lutzee,” to family and friends), cultivated a reputation as a raconteur. Varady grew up on Laci’s stories of business prowess in pre-war Budapest and survival during World War II – all of which Laci attributed to his quick wit, connections, and fierce determination, plus a pinch of luck.

Later in life, at his son’s urging, Laci recorded many of these evocative tales on paper.

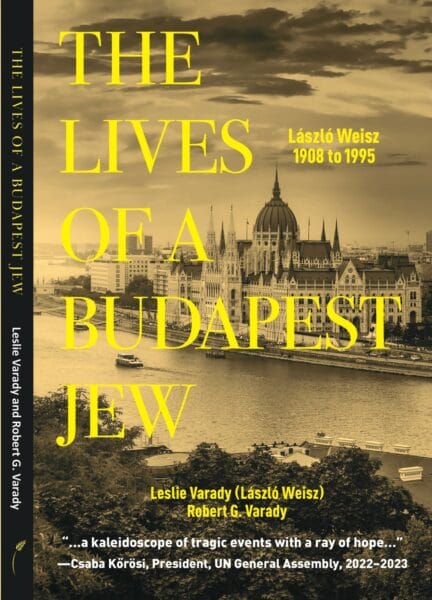

Now Varady, a University of Arizona research professor emeritus, has compiled these accounts into a gripping memoir, “The Lives of a Budapest Jew: László Weisz 1908 to 1995,” augmented by stories Laci’s Hungarian friends wrote for his 75th birthday celebration, letters, and more, including a 1987 video interview Varady conducted with both of his parents. Varady picks up the narrative from the post-war years in Hungary, to a sojourn in Paris, and ultimately to the U.S.

The degradation and deprivation Laci endured before and during World War II are not unique, yet the particular details of his travails and escapes make this story fresh.

As the book’s back cover notes, “Had he lived in unremarkable times, his life might have qualified as a Hungarian Horatio Alger story. But the Nazi takeover of Germany inspired a series of anti-Jewish laws in Hungary. Laci’s employer offered him a choice: accept a demotion and reduction in salary or be fired along with the other Jewish employees. He chose termination, resolving to find a better life for himself and his family in a more welcoming nation. Unfortunately, World War II intervened. Only after surviving multiple forced-labor camps and escaping imminent deportation to a death camp would he achieve his goal.”

Laci recalls his first forced-labor camp as “relatively benign.” After the first month or so, he was even allowed to go home at night to his wife. But in relating his second call-up to the forced labor battalion, known as the Munkaszolgálat, he reveals the indelible horrors of that time in a quick, parenthetical comment: “and in my mind, I am still not released today!”

Varady was born in Budapest in 1943 and lived through the last years of the war as a baby and toddler, including near-starvation in the Budapest ghetto with his mother, Magda. But his earliest memories are of traveling with her by train to Paris in 1947, where his father had preceded them — an experience, Varady says, that led to his lifelong wanderlust.

Laci’s friends mocked him for leaving a country they believed the communists had rescued from fascism. But Laci had noticed that most of the lower-level bureaucrats, officials, and police officers who now wore uniforms with red stars “were the same individuals who, not long before, had worn the insignia of the Arrow Cross regime. The same individuals who had taunted and cursed him and his fellow forced laborers.” For him, staying in Hungary was not an option.

The family enjoyed Paris, where several of Laci’s brothers had settled before the war. Varady learned the language quickly, excelled at school, and enjoyed freedom undreamt of for a child today, spending bucolic vacations in a small town south of Paris with the Gauthiers, a family his parents had exchanged letters with but never met before they sent Varady, age 5, off on a solo bus journey to their home. Fortunately, the Gauthiers were kind, generous people whom Varady soon viewed as Tonton (uncle) Émile and Tata (aunt) Suzanne. But Laci’s ambition led to one more emigration. Exploiting a loophole in U.S. immigration law that he learned of through one of his many connections, in June 1952, the family sailed for America, where Laci had many second and third cousins.

Starting over in America wasn’t easy, yet by the time he retired as a comptroller in 1965, Laci had reclaimed the bright career he’d started in pre-war Budapest.

For Varady, “The Lives of a Budapest Jew” came together with surprising speed and ease, even though he began without an outline, unheard of in his professional books and articles. He has found that most readers, even non-Jewish readers, find a way to relate the memoir to their own lives.

“It winds up being a sort of mirror to people,” he says.

Hungarian Ambassador Csaba Kőrösi, a former president of the UN General Assembly, called the book “a heartbreaking kaleidoscope of tragic events with a ray of hope.” Varady was especially moved by the last lines of Kőrösi’s endorsement, “An excellent reading, a lot to be learned from. For me too, who was the first Hungarian ambassador at the UN to apologize for the Hungarian Holocaust.”

Varady will hold a book launch for “The Lives of a Budapest Jew” on Thursday, Sept. 18, at 6 p.m. at the Tucson Jewish Museum & Holocaust Center.

The book is available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Wheatmark, and other vendors.