Four Tucson Jewish community professionals, Ital Ironstone and Nate Weisband of Jewish Philanthropies of Southern Arizona, and Sophie German and Jessica E. Mattix of Jewish Family & Children’s Services, traveled to Israel for a Jewish Federations of North America LGBTQ+ Pride Mission June 8-12, joining almost 100 leaders from across the continent on a journey of discovery and connection.

The five-day intensive program included tours of LGBTQ+ health and community centers along with heritage and Oct. 7 memorial sites.

“This mission exists because Jewish Federations of North America believe LGBTQIA+ Jews deserve to see themselves reflected in Israel’s story right now, when it matters most,” the organizers noted in their welcome materials.

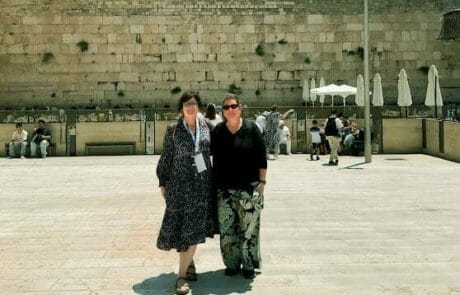

German and Mattix were both visiting Israel for the first time. It was the sixth trip for Ironstone and Weisband, although their first time traveling together.

The mission concluded the night before the annual Tel Aviv Pride parade was scheduled to take place.

German and Mattix, who had opted not to extend their trip, returned home June 12 on one of the last flights to leave before Israel closed its airspace due to its preemptive strike on Iran and potential retaliation.

Ironstone and Weisband had planned to attend the parade. Instead, they shared in the quintessentially Israeli experience of nights spent running to shelters (after relatively calm days on the beach or visiting friends and family) before each made their way home to Tucson, with help from JFNA contacts.

It felt like two separate trips, says Weisband, JPSA’s young leadership manager, who adds that the mission portion was incredible.

For him, a group visit to the Yitzhak Rabin Center on the first night emphasized the mission’s importance in a post-Oct. 7 world where antisemitism has become more common, especially in otherwise progressive communities.

“Jewish Zionist queer individuals have been excluded from queer spaces and pride parades and really made to feel othered in a community that has themselves been othered,” Weisband explains. “So to be with almost 100 Zionist queer Jews was unlike anything that I ever really thought I would get the opportunity to be a part of.”

Mattix, director of marketing and communications for JFCS, noted that the mission’s first full day included a visit to Kibbutz Nir Oz, where one in four people was murdered or taken hostage on Oct. 7.

“Seeing the aftermath of what happened on that day was both extremely difficult, obviously, to relive, but extremely moving. And I was really struck by the resilience of the people,” she says.

Listening to survivors’ stories was difficult, agrees German, JFCS director of older adult and community services. “But I think it was important, just as important as hearing our Holocaust survivor stories.”

Along with other mission participants, the Tucsonans toured Nir Oz with a former resident, Clarice, who spoke of the lingering trauma for community members, including her son, who was the chief of the kibbutz security team.

“One other thing that she said that was echoed time and time again on the trip was that Israelis can’t find closure until the hostages are returned, every single one of them,” Weisband says. “As an American, and being in the Diaspora and being so removed from Israel, you understand that on a more intellectual level and even in your heart. But there, it’s very visceral.”

The tour also included visits to the Nova music festival memorial site, Hostage Square in Tel Aviv, and the “Pillars of Eternity” memorial in Sderot, on the site of a police station that was destroyed after being infiltrated by Hamas on Oct. 7.

The threads of the mission intersected, Weisband said, when they met Omer Ohana, who became a gay rights activist after his partner, Sagi Golan, a decorated IDF officer, was killed in battle on Oct. 8. Although the IDF has recognized the rights of same-sex and common-law partners of fallen soldiers since the mid-1990s, Ohana led a succesful campaign for this recognition to be enshrined in law.

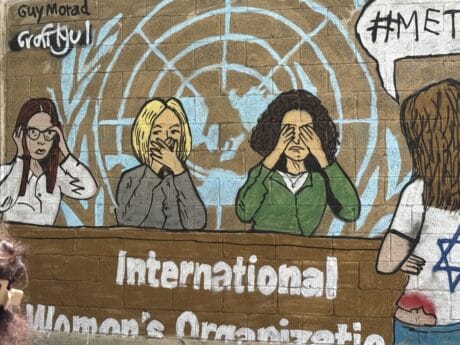

For Ironstone, JPSA women’s philanthropy manager, memorable moments of the mission included meeting survivors of the Nova festival at a government-funded Tel Aviv rehabilitation center; hearing a trans combat soldier describe her choice to join the security forces as a way to shift how authority treats marginalized communities; and seeing the street art across Tel Aviv, “bold, defiant, and heartbreaking messages that can often communicate the emotional reality of war better than any statistic or news article.”

She learned that the Tel Aviv LGBTQ Center is the only such center in the world to receive government funding and that some 10% of the Israeli population identifies as queer. In her notes from the trip, there are more fascinating facts and figures “that I’m very excited to go through and process intellectually,” she says. But the traumatic days following the mission left her feeling somewhat numb.

On her first trip to Israel at age 14 — funded by reaching out to the Tucson Jewish community — Ironstone saw that many aspects of her “alternative” upbringing, such as growing vegetables and optimizing recycling, are part of ordinary life in Israel. “Oh my gosh, these are all my people,” she remembers thinking, “except you’re not called a hippie there. You’re just called an Israeli.”

Like Weisband, Ironstone feels that in the U.S., her Jewish and queer identities “often feel like a political statement.” She has been out for only a couple of years and wouldn’t feel comfortable attending a pride parade anywhere but Israel, knowing that in other places she could face “anti-Zionist people yelling at me about wearing a Jewish star.” But in Tel Aviv, she felt free to experience all the facets of her identity without conflict.

Sirens and Safe Rooms

“I was having an expansive, spiritual moment,” Ironstone says of the night of June 12. After hours spent exploring Tel Aviv, she had just returned to her hotel room and opened the door to the balcony when she heard a siren, which came as a surprise because she hadn’t received any notifications on her phone.

In the hotel hallway, she saw all the Americans running around, “all these crazy directions. I kind of felt like it was my job to take the lead, because there were no Israelis around,” which made her feel even more afraid. The hotel had safe rooms on every floor, but some people felt they’d only be safe in the basement.

The war was not cinematic moments or even as loud as she expected, she says. “It’s more of a deep, lingering fear.”

Weisband was at a Pride party when people’s phones began buzzing with Home Front Command notifications warning that something would happen soon. There were no taxis, and since they had not heard sirens, he and five others walked for 45 minutes back to the hotel.

“I was very scared because we weren’t in a safe room, and nobody knew what was happening,” he says. He never heard a siren, so he went to his hotel room and slept. The next day, he and Ironstone checked out of the hotel and went to friends’ homes.

“It wasn’t until Friday night, around 9 p.m. that Iran counter attacked, and that started for me, 10 or 11 days of in and out of safe rooms, basically nonstop,” he says, noting that Israelis, who are used to finding joy amid fear and sadness, weren’t as frightened as he was.

“The fact that we could go into a safe room and listen to someone play the guitar and have a group of a dozen Israelis around us singing a song was actually very comforting,” Weisband says.

After that, he went to a cousin’s house in a Tel Aviv suburb, where the safe room was their four-year-old daughter’s bedroom. Amazingly, she slept through all the noise, he says.

He also got to enjoy extra time with family in Jerusalem.

Making their way home

Weisband and Ironstone each flew home via Jordan, on different days, with assistance from JFNA contacts on both sides of the border. Weisband recalls a five-hour wait in stifling heat to get through security. Ironstone’s wait was shorter, but both had been cautioned to leave Jewish identifying possessions, such as Star of David necklaces, behind in Israel.

Weisband’s route home took him from Jordan to Qatar. It wasn’t until he was on the flight from Qatar to Los Angeles and got Wi-Fi — and frantic texts from family and friends — that he learned that Qatar had closed its airspace in response to the U.S. bombing Iranian nuclear facilities on June 21.

Ironstone, whose luggage was thoroughly searched in Jordan, was also glad she’d removed any queer paraphernalia, such as flags, rhinestones, and glitter.

But she was struck by the irony that only days after celebrating the meshing of her Jewish and queer identities, she had to hide them from the Jordanian authorities.

Ironstone didn’t cry until she booked her flight from Jordan. Her tears weren’t from relief, she says, but from the sadness of being forced to leave a place she calls one of her homes, and the helplessness of knowing she could no longer be there in person to check in on the people she loves.

“That loss of control reminds you how small you are,” she explains, adding that she wonders how generations of mental turmoil have impacted Israelis.

Believing it is her responsibility to use her experiences to make a positive impact, Ironstone says, “I have not felt more grateful to be in a fundraising position for Israel than I did when I got home.”

German says the mission strengthened both her Jewish identity and her connection with Israel. It was also the first time she was involved with the LGTBQIA community “in a big way.”

“It was good to see how Israelis are working within their system to make broad systemic changes that will have meaningful impact for LGBTQIA+ people amidst a very conservative government,” she says. One example is that Israel’s universal health care covers everything that a trans-identifying person would need for medical care, behavioral health care, and any kind of surgery.

With JFCS’s focus on providing trauma-informed services, Mattix was intrigued by the variety of therapeutic approaches to trauma in Israel.

“There was a lot less talk therapy, which I think makes sense when you’ve gone through something that’s so traumatic, and there was a lot more of mind/body sort of physical activities, like dance therapy, or art therapy, that kind of thing,” she says.

She adds that seeing the way Israelis “really wrap their arms around the LGBTQ+ community” gave her ideas about how JFCS might better work with other agencies to provide more integrated wraparound services.

“Having gone on such a meaningful trip, it really gives you, or at least me personally, sort of a renewed energy to do the work that we do,” Mattix says.

Weisband says he is not sure why he needed to experience the terror of war. But would he go back to Israel?

“In a heartbeat,” he says.